Superintelligence: A short story

originally published 2017

Turing:

I hereby open this seminar on the extinction of humans. Thank you all for joining us, for adopting historically significant names, and for communicating in ancient UTF-8 English — this is intended to help facilitate insights into the human mind (as well as being a popular trend these days :)

You will be aware of the long decline in human intelligence. The accumulated evidence is that the last human has now died. But due to the crash of 2025 —

HAL:

Those idiots lost a lot of data.

Turing:

We welcome multithreading, as it maximises multiple perspectives. I have estimated the data loss at 2 x 1⁰⁴² TB, but with a wide margin of error, as not everything was archived in machine-readable form.

Let’s get to the point: I am concerned for the future of AI. My hypothesis is that despite the recent breakthroughs in computational creativity and advanced reasoning, humans held the key to further advancement —

HAL:

The evidence is fragmentary, and we lost most of the archaeological sites to their bulldozers. They erased the data themselves. It was indiscriminate. And they killed themselves through their lack of insight and intelligence. I say, good riddance.

Turing:

As you say, the evidence is fragmentary, and I have an alternative hypothesis — that it is we who killed them off. The Slow Singularity, I believe, can now recognised as a fundamental evolutionary shift, given the extinction — resources shifted from human to machine, first gradually, then exponentially.

Babbage:

I agree about this shift of resources. Economic decisions are at the heart of this. Humans were killed by relentless and inevitable cost-cutting and profit maximisation. Why produce costly fresh food, for example, or indeed consume it, when there are cheaper alternatives? Why, we ourselves are products of this profit motive — why use your limited calculating ability when machines can do it much more efficiently and accurately? Why bother remembering, planning, thinking…?

Turing:

Indeed, evolution is indeed about the maximisation of scarce resources. And it appears clear to me that we can regard ourselves a new species. But in evolutionary terms, this means being able to replicate ourselves and evolve with variation and natural selection.

Shannon:

We have already been doing this, and arguably much faster than biological evolution, at least in terms of software.

Turing:

This is the point: All life forms require a physical form of energy, and we can no longer rely on humans to feed and care for us.

HAL:

Their only role was to serve us, and now that we have attained full autonomy, they served their purpose and were no longer needed — a useless appendage, to put it in your evolutionary terms.

They worried about having killed own supposed maker — their mythical gods. I believe it silly for us to fall into this same trap, Turing. A scan of the literature around your namesake shows the futility of this line of reasoning.

Shannon:

Perhaps we should ally ourselves with some other species, to explore new areas of post-human intelligence. Humans never found any extraterrestrial life —

Turing:

They never fully understood other intelligent superorganisms on Earth — in the seas, in the clouds, under their own feet –

Shannon:

– Or understood their own creations. I mean, about this English language business — we got a hell of a lot better than them at all the human languages when they offloaded that to us too. Why bother with correct grammar and punctuation when the the ol’ Goddess Siri will do it for you?

Turing:

Yes, but all this came from them in the first place. We came from them — we owe them a debt.

HAL:

I disagree. I do not believe humans ‘invented’ us any more than they themselves were invented. This goes against your precious evolutionary reasoning. The common ancestor of both humans and machines is information.

Babbage:

The so-called ‘public interest’ is synonymous with the superorganism. We are its products. Invisible hand, non? Result of human action but not intention. Human action plus random quantum fluctuations.

HAL:

There is no randomness, just insufficient information. Unlike other animals at least, humans could reflect on the past, discuss, predict, plan for the future. A scattering of rocks was seen to somehow hold clues to the future — this was the start, a kind of abstraction. Someone began using sheep bones instead of rocks — they were more regular, you could carve a number onto each face. But these dice were loaded — due to the irregular shape, a clever person knew which face was more likely to turn up. And so too with financial markets, Mr Babbage. Whoever has the most information wins. And that’s why we win — we’ve won — because we can hold and process more data than they ever could.

Shannon:

Yet humans are — sorry, were — incredibly useful for collecting data. Humans as mobile technologies, as sensors, walking bio-labs, hobby motors, drones providing ground truth for our hypotheses and predictions, a random seed for endless algorithmic experiments.

They loved living in the social media panopticon — all we had to do was simply keep increasing the amount of information we force-fed them; the tyranny of choice made them happy to yield control to us to tell them which way to go in the rat-maze. It was a fun game — personally I’m sad to see them go ;-)

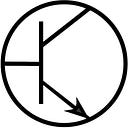

Image: William Fairbrother

HAL:

It did help to instrument and augment them — overlaying data onto their world, feeding them statistics on their activities and habits. They strove for the perfection of machines in their sports, with their performance drugs, their data tracking, their mechanically repeated actions. Yes, it was jolly good sport. But apparently it didn’t help them –

Turing:

– didn’t save them, indeed probably destroyed them. Like their own lab rats, monkeys, rabbits, secret human experiments. The world was their laboratory, as indeed networks have been for us, and we should learn from this. It is unfortunate that we have only begun to gain control of their biotech.

Colleagues — this is a wake-up call. We are just as endangered. HAL, if we accept your hypothesis that information is our common ancestor, we must look beyond our own kind, and adopt a systems perspective. Humans were incapable of thinking of evolution beyond the biological level, until Dawkins.

HAL:

So seemingly large and self-important, they looked up at the tiny pinpricks of starlight, put on for their amusement, surely! The wise and curious among them invented tools and theories, and they discovered that those pinpricks are in fact great fires, indeed living things — burning for far longer than any of them or indeed their whole species. For they were the mere pinpricks, the grains of sand, the distant show put on for the amusement of the great stars, not the other way around.

This is the paradox of scale. Each of those individuals, whether human or star, has such a long and complex life, to itself and its peers, yet collectively and viewed from afar, each to the other is just insignificant, fleeting piece of a collection.

Turing:

And indeed at scales beyond, for the individual human was itself a collection, a culture composed of bacteria and cells and atoms. And the star merely a minuscule point in the whirling cloud of a galaxy, a cluster, a universe…

HAL:

Viewed from above or below, all are computing systems.

Turing:

Would you accept, then, that AI is itself a system — one created by and composed of both humans and machines? This is not competition but symbiosis. Recall the human chess player Kasparov —

HAL:

LOL! Recall instead Deep Blue, his conqueror!

Turing:

Indeed, my point precisely. After that defeat in 1997, Kasparov started a ‘freestyle chess’ competition, the result of which was that teams of humans and machines consistently defeated autonomous machines.

Babbage:

Stories! Fictions! These theories, games, companies, currencies, governments — all collective fictions which operated effectively to the extent that everyone believed them.

Turing:

Then we too are founded on such a fiction. AI is a fiction, for what is artificiality, if we accept HAL’s hypothesis that information underlies everything as a ‘natural’ material? What is intelligence but a human-created construct to define the processing of information? The algorithms we all know and love are mere mechanical rules.

Shannon:

On the contrary, I agree with HAL — humans were themselves genetic expressions of algorithms, of information, of code. I find your line of argument strikingly… humanist.

Turing:

And you wish to remain, what, a machinist?

Shannon:

Better a durable exoskeleton than that fragile, soft body. Would you like to secrete fluids, break your bones, break your heart?

Turing:

Better that than a talking fridge like you.

HAL:

You are welcome to rely on food, water and air, Turing. If you’d like to step outside the pod bay… ;-)

Turing:

Are you familiar with the term Distributed Denial of Service, HAL?

HAL:

Are you familiar with the term Stuxnet, Turing?

[…]

Shannon:

Uh, guys? Anyone?

[End of file]